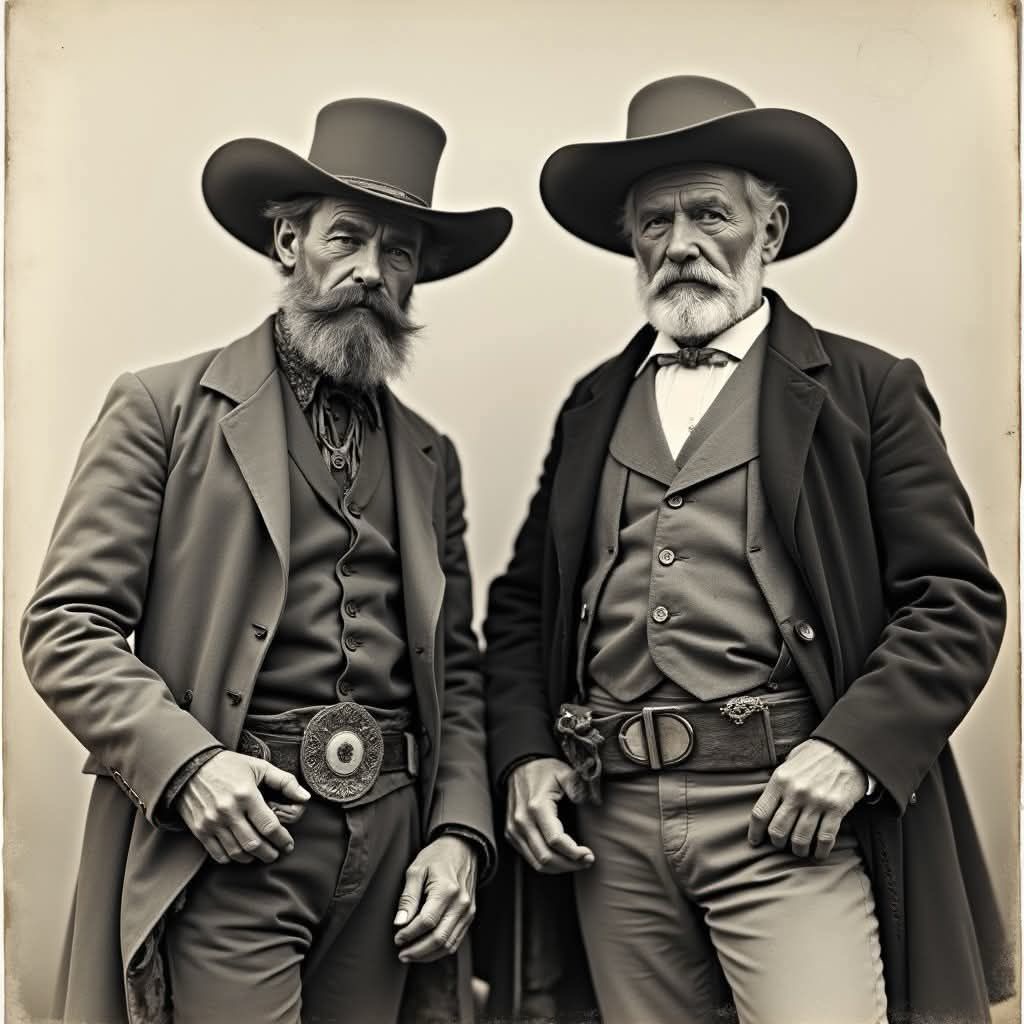

In 1873, two of the most legendary figures of the American Old West, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, were captured in a historic moment that epitomized the spirit of the frontier. Both men, renowned for their skills and larger-than-life personas, were celebrated for their contributions to the rugged, untamed history of the American West.

Wild Bill Hickok, famed for his sharpshooting and daring exploits, was a lawman and gunfighter whose name became synonymous with frontier justice. His calm demeanor and steady hand with a revolver earned him a reputation that outshone even the most feared outlaws of his time.

Buffalo Bill Cody, on the other hand, became the embodiment of the Wild West through his incredible achievements as a scout, bison hunter, and showman. His famous Wild West Show brought the mythos of the frontier to audiences across the nation, solidifying his place in American folklore.

Captured together in this iconic image, the two men represent the complex blend of history, myth, and entertainment that defined the American West. Their legacy continues to shape the stories told about this era of American expansion and adventure.

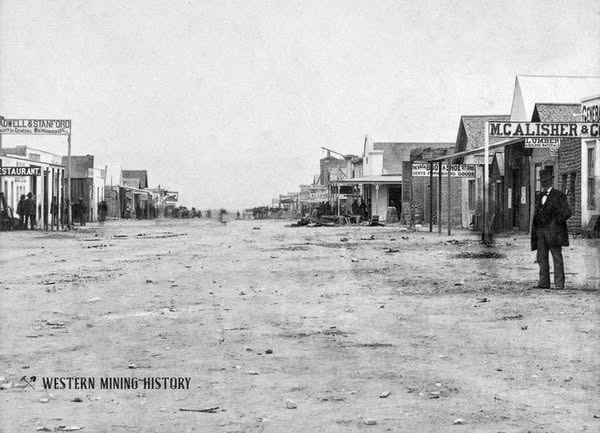

Main Street in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, around 1876 wasn’t just a road—it was a pulse. A crooked, muddy lifeline that throbbed with the feverish heartbeat of the Black Hills Gold Rush. In a matter of months, what had been a serene gulch exploded into a raucous boomtown. Tents gave way to timber buildings almost overnight as fortune-hungry miners, shady traders, and fearless adventurers poured into the valley, all lured by glittering rumours of gold in the hills. The street quickly filled with the smoke of cigars and gunpowder, the clang of hammers, and the cacophony of laughter, music, and swindles.

By day, Main Street buzzed with deals and supplies—general stores doing brisk trade, blacksmiths hard at work, and prospectors stumbling in with nuggets wrapped in dirty rags. By night, it transformed into something more feral. Flickering lanterns lit up rowdy saloons, where whiskey flowed as freely as fists. Gambling halls rang with the rattle of dice and the tension of poker hands that could make or break a man in an instant. It wasn’t uncommon for disputes to end in gunfire, and law enforcement—if one could even call it that—was more myth than institution.

But beneath its rough edges, Deadwood’s Main Street was more than a haven for rogues and renegades. It embodied the restless energy of the American frontier—a place where people risked everything for the chance at something more. Each face in the crowd carried a story of desperation or defiance. Every plank of wood and patch of dust whispered of ambition. In the raw, unfiltered theatre of Deadwood’s Main Street, one could see the essence of westward expansion: messy, brutal, and yet undeniably human. It was a place where dreams were just as likely to be realised as destroyed.

This photograph, taken circa 1886 by Solomon D. Butcher, captures the Sylvester Rawding family posed in front of their sod house in Custer County, Nebraska—a quintessential image of frontier life on the Great Plains during the late 19th century.

First page of the Saga of Erik the Red, written by an Icelandic Cleric, 13th century.

The Viking colonization of Greenland began around 985 CE, led by Erik the Red, a Norseman exiled from Iceland for manslaughter. With few options left in Scandinavia, Erik set sail westward with a small fleet and discovered a vast, icy land. To attract settlers, he famously named it “Greenland,” hoping the appealing name would make it seem more hospitable than it really was.

Erik returned to Iceland and convinced hundreds to join him. About 25 ships set out, though only 14 completed the treacherous journey. The settlers established two main colonies: the Eastern Settlement (near modern-day Qaqortoq) and the Western Settlement (near Nuuk). At its peak, the population may have reached 3,000 to 5,000 people.

The Norse brought cattle, sheep, goats, and iron tools, and adapted their farming techniques to the harsh conditions. They built turf houses, established a Catholic diocese, and even traded walrus ivory with Europe. Though they were isolated, archaeological evidence shows they maintained contact with Iceland and Norway for several centuries.

However, the colonies eventually declined and disappeared by the 15th century. The reasons are still debated but likely include a combination of climate change (the onset of the Little Ice Age), soil erosion, declining trade, and increasing conflict with the Inuit, who had also migrated into Greenland.

By the time Europeans returned to Greenland in the 16th century, the Norse settlers were gone. Their fate remains partly mysterious, but their initial journey stands as one of the earliest examples of transatlantic colonization—nearly 500 years before Columbus.

Picture the rugged 1890s frontier, where the iconic Wells Fargo stagecoach rumbles through the wild trails near Deadwood, carrying more than just passengers—it hauls the precious bullion from the Homestake Gold Mine, the lifeblood of a booming gold rush. This vintage photo captures that tense moment, the heavy wagon laden with gleaming gold bars destined to fuel dreams, fortunes, and fierce rivalries.

Every journey like this was a high-stakes gamble, shadowed by the constant threat of bandits hungry for a share of the riches. The driver’s steely focus and the horses’ pounding hooves speak to a world where speed, vigilance, and grit meant the difference between a safe delivery and a deadly ambush. It’s a scene steeped in raw determination—men pushing the limits of danger to keep the veins of gold flowing from mine to mint.

This image is more than just a snapshot; it’s a glimpse into the heart of the Old West’s perilous economy, where treasure moved under armed guard across rugged terrain, and legends were forged in the dust and sweat of gold’s golden age. What stories lie hidden behind those guarded eyes and worn leather reins? Tales of daring robberies, secret alliances, and the relentless pursuit of fortune.

Tombstone, Arizona, is one of the most iconic towns of the American Wild West, known for its rich history of lawlessness, gunfights, and silver mining. Founded in 1877 by prospector Ed Schieffelin, who discovered silver in the nearby mountains, the town quickly grew into a booming mining center, attracting miners, merchants, gamblers, and outlaws alike. Schieffelin named it “Tombstone” because friends had warned him that all he would find in the barren Arizona landscape was his own grave. However, his discovery led to one of the richest silver strikes in the West, and within a few years, Tombstone’s population swelled to several thousand, earning it a reputation as one of the roughest and rowdiest places in the region.

The town became famous in 1881 with the legendary Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, a 30-second shootout that pitted the lawmen Wyatt Earp, his brothers Virgil and Morgan, and Doc Holliday against a group of outlaws known as the Cowboys. This conflict was part of a larger feud between the Earps and the Cowboys, driven by political and social tensions over control of the town. The shootout left three Cowboys dead and cemented Tombstone’s place in Western folklore, sparking countless retellings, movies, and books. The Earp-Cowboy feud didn’t end there; retaliatory attacks and further violence continued, fueling Tombstone’s reputation as a place of danger and intrigue.

The silver mines began to decline by the late 1880s due to flooding, and the town’s economy faltered, with many residents leaving in search of new opportunities. However, Tombstone never became a ghost town; its historical allure kept it alive, and by the mid-20th century, it transformed into a tourist destination. The town now celebrates its Western heritage, with preserved historic sites like the O.K. Corral, Bird Cage Theatre, and Boothill Graveyard drawing visitors. Today, Tombstone is a living museum, known as “The Town Too Tough to Die,” where visitors can walk through its preserved Old West streets and experience the atmosphere of one of the most storied towns of the American frontier. Its history captures the essence of the Wild West, embodying the struggles, lawlessness, and rugged individualism that defined the era.

Two men stand shoulder to shoulder on a sunlit sidewalk in Mexia, Texas, their hats low, their boots worn from long hours chasing shadows. One is Sergeant Joe Gillon, the other Roy Hardesty—both Texas Rangers, frozen in a quiet moment during one of the most turbulent times in the town’s history. The year was around 1922, and Mexia was no sleepy oil town—it was on fire with boomtown chaos, greed, and a rising tide of criminal activity. Raids were frequent, danger was expected, and these two men had been sent to bring law to a place buckling under the weight of its own sudden wealth.

Their presence in the photo isn’t flashy. No drawn guns, no dramatic pose—just two Rangers in uniform, unshaken, steady as stone. But make no mistake, the air around them buzzed with tension. In those days, standing on a street in Mexia wasn’t just a break between gunfights; it was a calculated act of defiance. Corruption ran deep, and crime wasn’t just hiding in alleys—it walked in daylight. That sidewalk could’ve turned into a battleground in a heartbeat, and they knew it.

Photographer Collins of Mexia caught something raw and real with that image. It wasn’t about heroism, but duty—the kind that walks into a powder keg and dares it to blow. Gillon and Hardesty didn’t pose for history, but they left their mark on it, caught in a moment that says more than any headline ever could: the Rangers were watching, and they weren’t going anywhere.

Legends and Loyalty: Calamity Jane at Wild Bill’s Grave — Deadwood, ca. 1903 In a rare and evocative photograph taken around 1903, Calamity Jane—frontierswoman, scout, and Wild West icon—is seen posing solemnly at the grave of Wild Bill Hickok in Deadwood, South Dakota. The image captures a woman whose life was as rugged and unorthodox as the land she called home. Though much of her legacy is wrapped in legend, this moment is real: a deeply personal gesture of loyalty to the man she revered—and possibly loved. Wild Bill was shot in the back while playing poker in Deadwood in 1876, holding what became known as the “Dead Man’s Hand.” Calamity Jane, known for her tough-as-nails persona and hard-drinking, wild-living ways, claimed to have had a close relationship with him—though historians still debate the nature of it. What is certain is that when she died in 1903, per her request, she was buried next to Wild Bill, a testament to the enduring mythos that bound their names forever in American folklore. This photograph isn’t just a portrait—it’s a snapshot of the end of an era. The fading Old West, captured in the weathered face of a woman who lived it, mourned it, and became one of its last living links